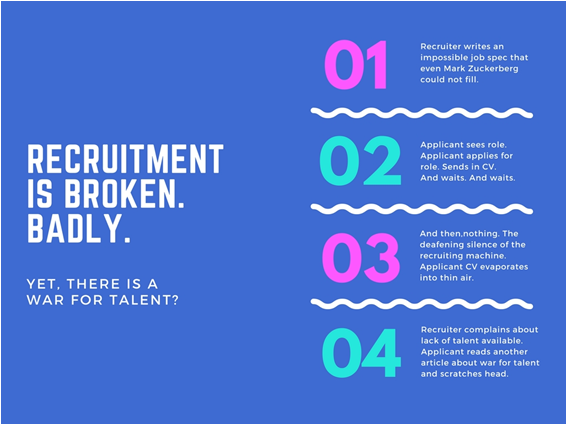

Ever applied for a job that you were perfect for, only for you never to heat from them again? And there is a ‘war for talent’?

Is it just me or does anybody else think that recruitment is broken? Many of you reading will have applied for a job, one that you thought you had the perfect mix of skills, qualifications and experience. And, you really wanted the role – so you had the right mix of motivation and attitude.

And then,nothing. The deafening silence of the recruiting machine.

Then you read another vacuous article about the ‘war for talent’, and the thought passes your mind: that you are not a talent worth fighting for! Management consulting firm, McKinsey, were responsible for the phrase – the ‘war for talent’. The Financial Times puts it beautifully: ‘as a metaphor, the war for talent takes the biscuit. The big thing about a war is that there is always an enemy, but in this case, there appears not to be.’

Another common experience is meeting a much-lauded marketer in the flesh, perhaps working for an iconic brand, and doing a role that you would sell your mother – and grandmother for. Then, you have had a quick look at their LinkedIn profile – and say to yourself, ‘I think I have better-suited skills, qualifications and experience for that job, so why does he or she have the job and not me?

Finally, you read about Talent Acquisition Managers, talent pipelines, and employer branding – all looking for ‘world-class’ talent. Having recruited a lot of marketers, I can tell you that most companies do not even know how to define “talent”, let alone how to manage it. It is truly sad and maddening that you hear complaints about “talent shortages” when anyone who has applied for a job knows that the standard corporate recruitment process is so broken. Indeed, the perennial skills shortage stems as much from firms’ sky-high expectations as it does from a dearth of manpower.

The Typical Recruitment Process

Let’s look at typical recruitment process. First, job advertisements are often so tightly written that there is possibly one person in the world that can do the job. Maybe Jeff Bezos or Mark Zuckerberg could do it – but they are not available, I believe. Or they are written with a 21 point list of mostly unrelated skills requirements: brand guru, combined with Adwords expertise, perhaps a bit of social media and, ideally a whizz with email marketing too. If you were hiring a carpenter, would you expect them to be an expert at plastering, proficient at rewiring and a competent at carpet fitting? Even if someone were available with 100% of the skills needed to do the job, they’d be unlikely to apply for it, as there would no development opportunity.

A subset of this is looking for an absurd amount of experience and skills for something that is brand new: a version of ‘only candidates with ten years Snapchat advertising experience need apply’.

Then there is screening: your CV is screened through some online recruitment sausage machine by searching for keywords. Somewhere along the line, recruiters decided that we could really tell the smart and capable people from the not so smart and capable people by means of keyword-searching algorithms. Now, clearing the algorithm hurdle is as important as being able to do the job. Of course, if you are lucky a recruiter might have trawled LinkedIn (searching for keywords, of course) and stumbled upon you.

On the assumption things move on a bit and you get selected for an interview, everyone has to be recruited according to the same template. Maybe the recruiter sets a test – the sort of ‘which square boxes go into which round holes’ type of tests that are supposed to show a level of intelligence. But these are a trap. By setting the same task, we recruit people who are carbon copies of each other. They will have the same skills and think in the same way. We all tend to see merit in people who and think like we do. We hire candidates primarily because they have personalities similar to their own. Opposites do not attract in the corporate world.

Poaching from Competitors

The most pervasive idea is that the only way to hire great people is to poach them from competitors or specific companies: looking for great brand people? Only hire from Coca-Cola, Diageo or Unilever. Even the Googles and Facebooks are not immune to this – despite their much-vaunted recruitment programmes with “secret sauces” for sourcing, analysing and evaluating potential hires based on data and statistical analysis of the makeup of their ideal hire. Try this exercise: check out how many people in Facebook, Google, LinkedIn, Microsoft, Twitter and Apple have worked for the other brands.

Finally, there is the straightforward bias towards what type of university you went to – a sort of signal that you know stuff. But knowing things is overvalued today. You can find facts on Google – the trick is knowing which source to trust.

Recruitment isn’t working

Let’s call it as it is: recruitment isn’t working. The vast majority of hiring decisions are made on gut feel, personal experience, who you know and corporate belief systems about the sort of person ‘hired round here’. ‘People are our most important asset’ is really an empty slogan.

It isn’t talent shortages that keep employers and willing and capable job-seekers apart. It’s the recruitment process making hiring decisions based on preconceived pedigrees. How many brilliant, high-potential people are not given the right opportunity to fully realise their potential and have a great career due to the craziness of the recruiting process?

What if we took all of these assumptions about recruitment and flipped it on its head? What would that look like? Well, there are examples from sport: if you’ve seen the movie “Moneyball” with Brad Pitt, about baseball, you know that that the ‘Moneyball’ strategy for winning relies on analytics, statistics, and numbers, rather than opinions, intuitions, or appearances. “Moneyball” player recruitment challenged conventional wisdom as to what top talent looks like and where it comes from. Just like Leicester City did when they won the Premier League by better understanding correlations through new forms of scouting, they uncovered hidden gems that made the team winners.

So, where should we start?

Wwhere should we start? With ourselves.Marketing leaders who are serious about hiring great people need to examine their own internal practices and fix whatever is broken. Get involved early and often. Remember, you are going to spend years of my life working, coaching and guiding them, so you have to be involved from the start. You have to read all the applications. Yes, all of them, not just the shortlist of HR or an algorithm. “You don’t put a team together with a computer” is a salient quote from “Moneyball”.

Drum the adage ‘hire for attitude and train for skills’ into your head. If they are right person, spend the money on a few courses to get their skills up to speed. Look for potential. Ask the question, do I really have to hire fully-formed employees from day one, rather than train up on the job? Think about the traits, accomplishments and information overlooked by traditional recruiting methods. With all the time you spend finding people with the perfect level of experience, you could have already trained someone who is eager and willing to learn. And, while you are at it, forget deadlines for applications. Really, you are serious about ‘talent’ but they have to find you by a deadline?

I have spent multiple evenings of my career reading through tonnes of CVs, the good – and the dross. But I don’t regret it, because I believe that, as leaders only we can truly understand the marketing challenges of the brand, and, therefore, only we can recognise the magical mix of attitude, drive and skills that make a great marketer. As they say in ‘Moneyball’, ‘the goal shouldn’t be to buy players, the goal should be to buy wins’.